A Wild Hunt: Nina Murashkina's "Her Beasts"

"Her Beasts" is showing at The John D. Mooney Foundation in Chicago until June 15th

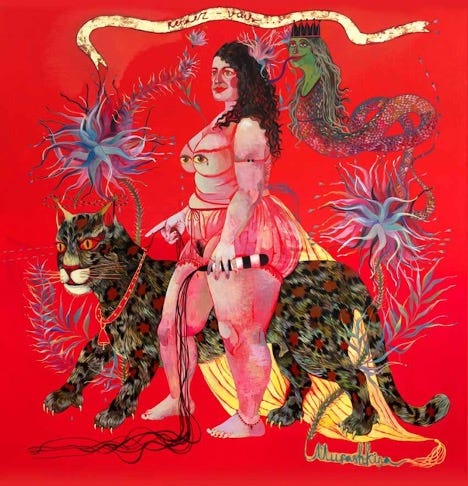

Nina Murashkina’s new art exhibition, “Her Beasts,” at the John D. Mooney Foundation in Chicago is well-worth checking out. According to some introductory remarks she offered those assembled at her opening on May 29th, her work is meant to depict a world where a woman shines and a man supports her—facilitating the glow-up. I could certainly see that reflected in some of the artworks on display: there are paintings and drawings in which a male cranium literally supports a woman sitting on top of it, for example. But I detected a certain impish irony in her remarks. It felt like there was something else going on in her visions, beyond encouragement to smash the patriarchy. These artworks aren’t limited to a political statement. They’re not a pamphlet in paint but significantly transcend that station, touching the magical and archetypal. It’s refreshing to run into artwork that quarries down to the subterranean level and gains access to the territory of wish and dream in an unfamiliar yet recognizable way. Primarily, Murashkina’s paintings transmit an erotic, pagan dream—or, quite often, a nightmare.

You can see this in a work entitled “Equality,” which spans an entire gallery wall. It made sense for it to take the ancient Chinese form of silhouette art, as what it depicts would be, perhaps, too strange, too unnerving, to leap into color and light. The shadow of a male hunter and the shadow of a female hunter both are engaged in the hot pursuit of the opposite sex. Silhouettes of detached penises shoot out shadow droplets and invisible eyes zero in on the lust object with targeted beads of passion. The quest of love and lust necessarily takes place in a mess of frenzied shadows. Here are shapes of longing cut out of the human body, sent off like hounds, engaged independently, mindlessly, on their own wild hunt. The silhouette depicts “equality” in that both men and women take an equal part in the hunt, but the hunt isn’t restrained by any norms of courtship. It’s a free for all. There’s a darkness to it, literally and figuratively.

Murashkina’s paintings are rich in art historical and mythological detail. We see fleshy women riding magical beasts, holding whips. The eyes that replace the nipples on most of the breasts in these paintings highlight the flesh as a surface of awareness, possessing its own kind of knowledge. This is knowledge, primarily, of suffering. So many of these nipple eyes are leaking tears. The body sees or—in the words of a popular book—“keeps the score.”

Murashkina provides some additional commentary on her work, which I find instructive: “In Her Beasts, I give form to feminine intuition — blue tigers, ghostlike horses, moon-eyed cats. These are not just creatures, but inner forces: fierce, tender, untamed. Through acrylics, paper silhouettes, and graphic lines, I build layered dreamscapes. Each Beast is a guide. Not to be conquered, but danced with.”

The mad frozen smiles on all the faces, rigid and clown-like, are by turns mesmerizing and disturbing. There is something somnambulistic and entranced about these figures. They are themselves sunk in myths and dreams, inviting us to follow them down sleeps’ corridors. They may wield whips and ride beasts, but one can’t escape the sense that the forces of passion surrounding them are greater than their own wills, that they are ultimately subservient to the beasts they are riding: the forces of love and death. Great Nature conquers and subdues all. The body may register its protest with an exclamation point or a question mark, but sex and sleep rule their kingdom without permitting dissent. Camille Paglia, the great apostle of “Amazon Feminism” in her epochal survey of Western art and literature, Sexual Personae, would recognize a kindred vision, I think.

One can pick out numerous art historical references that have found their way into Murashkina’s rich, multi-layered works. There are nods to the Ancient Greeks, to Picasso (someone at the gallery opening noticed a reference to Guernica), to Chagall, and to Eastern Orthodox iconography and Easter paintings. Some of the anemone-like vegetation felt almost Lovecraftian and alien. In Murashkina’s selection of sketches, I even noticed what appeared to be references to Hindu art—one winged creature looked like a mythical garuda.

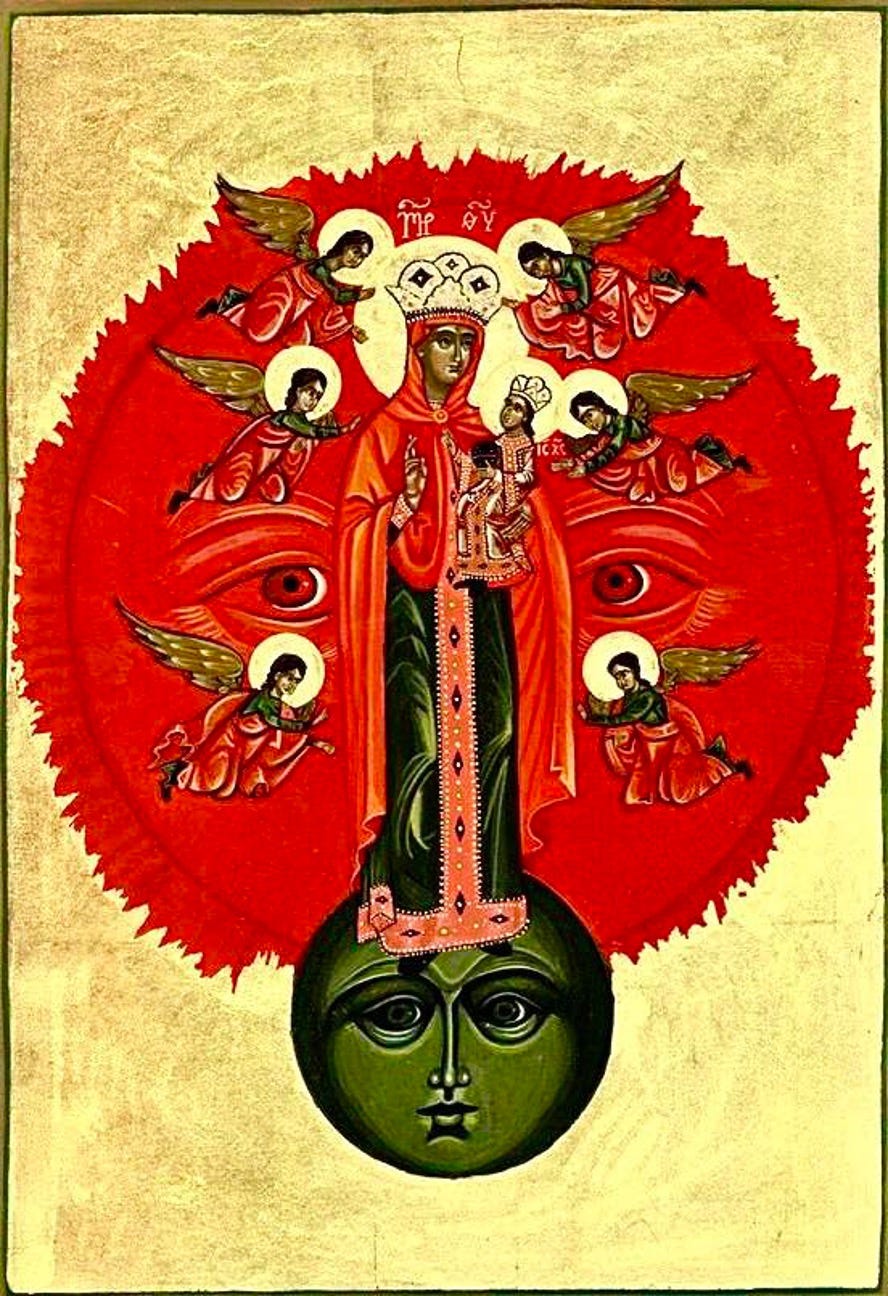

Murashkina is from Ukraine, and these varied influences are subsumed in a vision that is both personal and somehow unmistakably Slavic. Witness the notable use of gold leaf and red background, perhaps slightly reminiscent of Orthodox icons like this version of “The Woman Clothed with the Sun”:

Some of the paintings reminded me of a pagan transformation of icons of the Virgin Mary, featuring a distinctly non-virginal Great Goddess, while others riffed on fairy tales like Snow White and myths like The Birth of Venus. They give you the sense that Murashkina has managed to bring something personal out of the material of myth, has made it her own. The persistent use of red—the color of desire and experience, as opposed to white, that of innocence and naivety—also seems significant. (Murashkina wore what I have to assume was a traditional Ukrainian costume of some kind to the event. It was bright red. I wish in retrospect that I’d asked her about its meaning).

Murashkina is one of over a dozen Ukrainian artists to be featured by the John D. Mooney Foundation in recent years. Not only is the Foundation doing admirable work in highlighting artists from this besieged nation, but it is providing a fresh infusion of new blood, new perspectives. I’m admittedly a neophyte in art criticism and am relying on my own naïve judgments, but I appreciated the intensely figurative, mythical, and narrative forms of her work. As I’ve been frequenting galleries more, I’ve grown a little fatigued with works that are merely pure texture, that don’t hint at a story or incarnate a meaning. The magical feminism of Murashkina’s work more than fulfills this mythopoetic yearning on my part, resuscitating old stories with a new spirit, making them live again.

Her show runs for another week, until June 15th. If you’re a Chicagoan or happen to be visiting, stop by the John D. Mooney Foundation in River North and take a peek. You can find Murashkina’s art on Instagram.

Sam, super review! Thank you.

Very interesting!

Red is most likely is symbolic of the sun, fire, beauty, and blood before love and lust.